I am sitting at the Fat Lady Restaurant in Jack London Square with two friends. One friend grew up in a middle class family in Vallejo. Her mom is White and her dad is Black. The other friend is an upper middle class White woman who grew up in Suburban Denver and lives in Montclair. Then there’s me. An Indigenous Latina from a wealthy family.

A mixed crowd of three friends that reflects a tiny slice of Oakland’s vast diversity. Over wine and dinner, the conversation moves along different topics and we touch on redlining as I describe a documentary that my Oakland Voices mentor, Brenda Payton, created with others about mortgage lending called, “Your Loan is Denied.” I tell them about a quote Payton and her reporting partner got from a loan officer when they asked him why he didn’t approve home loans for families of color. “Because I didn’t have to,” he responded. One friend gasps, “When was that documentary made?”

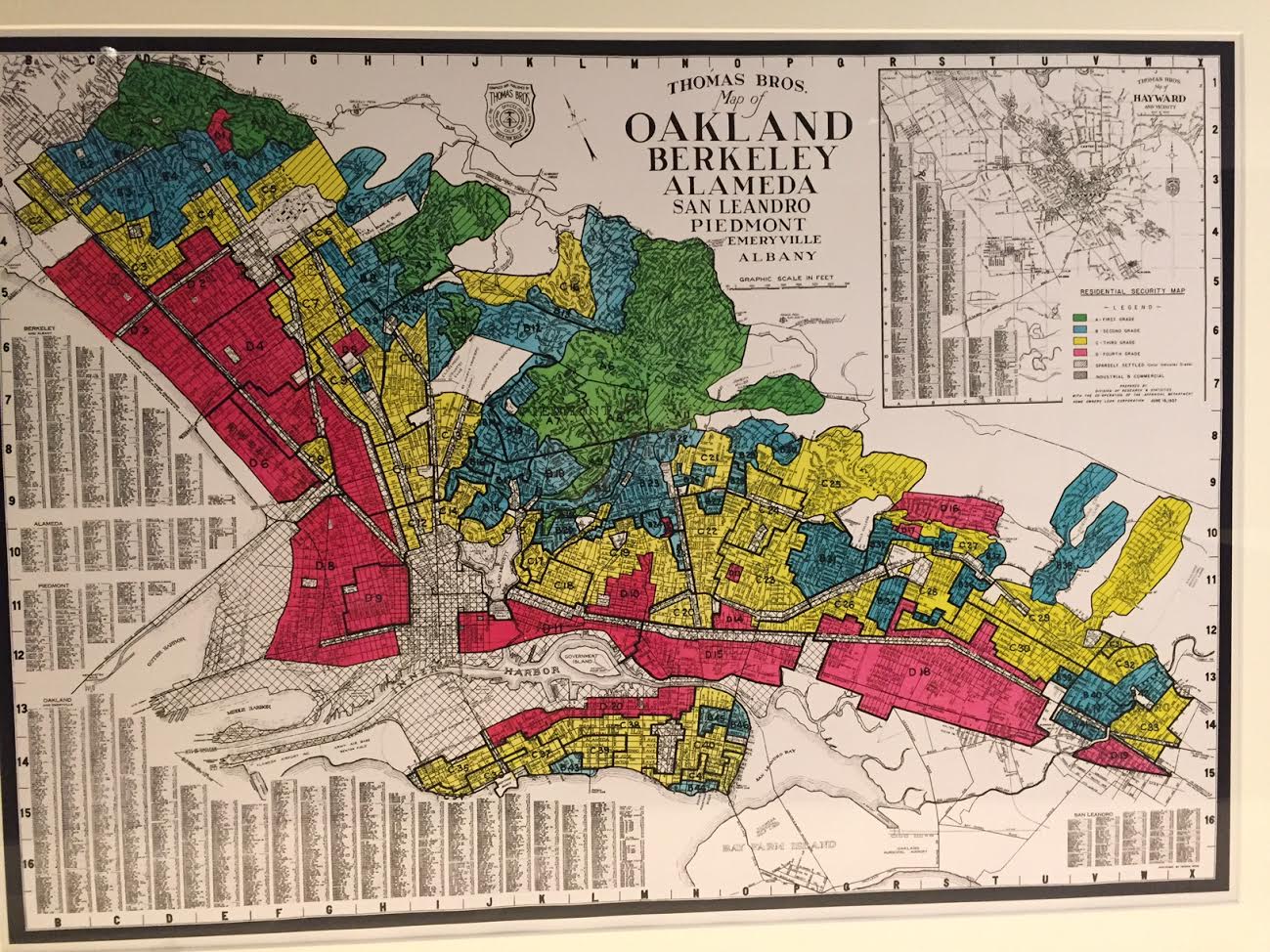

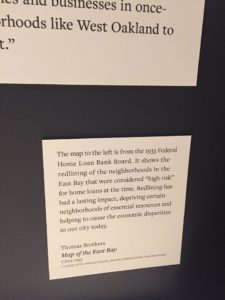

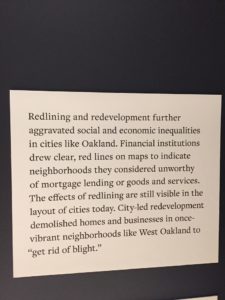

“In the ’90s,” I reply and she lets out a sigh of relief and says with finality, “Oh, so, a long time ago,” and settles into her seat. Annoyed by her reaction, I begin to launch into my experience attending the Black Panther exhibit at the Oakland Museum at the end of February where I saw the maps of redlined Oakland neighborhoods, created by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) that decreed neighborhoods worthy of investing and developing economically, or not. Neighborhoods with Black people, immigrants and other “low grade” populations were deemed unfit for investing. The vibe becomes tense at the table and someone quickly changes the subject.

Why is it so hard to accept that our society has evolved directly from how this country was founded—by the genocide of Indigenous nations, on the backs of enslaved Africans, and from the exploitation of immigrants? The HOLC maps were created in 1933, which was less than one century ago. Why is it such a difficult pill to swallow, that some of us are better situated to do well because of unearned social benefit—privilege? Why is it so hard to see the intersection of history, race, gender, social class and how these factors very much influence the power structures that exist today? Why do people take it so personally? Must our vision of the United States be so squeaky clean, that we pretend this land was a big empty that pioneers settled bravely and now we all have equal access to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness? Are we that uncomfortable with the messiness of truth that we do gymnastics to lie to ourselves and our friends?

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact reason why some neighborhoods in Oakland have more resources than others without looking at history through an intersectional lens. In an effort to simplify a complicated question, the answer is that societal structures are created by people with the most power, to benefit them directly. Then we like to pretend access to a baseline quality of life is equal, and if you don’t make it—there must be something wrong with you. You didn’t work hard enough. You didn’t pull yourself up fast or far enough. The fabric of Oakland challenges this simplistic idea. Oakland is rife with organizations, collectives and individuals that seek to deconstruct the layers of barriers that are unfairly posed in front of people of color, poor people, women and others that don’t benefit equally from current structures. I could comb through data to illustrate bureaucratic local governments that are insular and stagnant. But I’d like to focus on what I see and hear.

I’m back at the Fat Lady waiting for a friend. An older, White gentleman sits next to me at the bar and tells me about his commercial real estate business. He launches into a tirade about how Oakland has so many competing priorities, that its local government can’t get its act together. “You don’t see what happens in Alameda or San Leandro, happen in Oakland. Those cities have it together. They have more cops. More peace.” Interesting. I let him continue without interjecting.

I can’t pretend to know the solution to Oakland’s uneven distribution of resources. But I can point out that if you can’t name it, you can’t fix it. The unwillingness of people that can affect actual, systematic change, to name what exactly is going on: certain people have privilege because they are recipients of unearned social benefits, is a serious barrier to progress. It’s up to them to include others into the power structure. Or it will happen much more chaotically and violently.

I was musing about this with an Oakland Voices colleague—about how people in power will harm others, to their own detriment, to keep others down. We are such a wealthy society that it’s possible for everyone to have a baseline of wellness and the rich can still be rich. But they’d rather suffer to keep others down.

That said, can Oakland find common ground and reach across systems and lines to move forward in a more equal way? If we continue to refuse to name the truth, we are in danger that mounts with each passing day.

Sandra Tavel lives and works in East Oakland. Emigrating from La Paz, Bolivia and growing up in suburban Denver shaped her desire to put roots down in a place that is diverse, politically progressive and rich in social justice oriented history. This journey brought her to Oakland, which gets a disturbing and bizarre rap on much of the media that exists today. She’s looking to move the needle to create different narratives that reflect the complexity and nuances that make Oakland what it is.

She has been an avid writer and voracious reader her whole life. When she’s not working, reading or writing, you can find her at yoga class, hiking the Redwood Regional Park System or playing on the beach with her partner and two dogs.

Be the first to comment