Ericka Huggins, the activist, educator, and poet, begins her class at Merritt College “The Black Panther Party: Strategies for Organizing the People” by having students gather their desks around in a circle. She reminds them to turn in their extra credit on this final day of lecture.

Though review of course material was on the agenda, the class instead falls into a powerful group discussion on the recent killings by police of Eric Garner and Michael Brown. Some students share their own stories of violence committed by police. Some tears are shed. “We talk about our lives in that class, not in a disconnected, abstracted, cerebral ‘somebody else’s history’ or ‘somebody else’s current experience’ way,” Huggins said later.

After one student shares a particularly harrowing story of his aunt who lost her son to police violence, Huggins asks him to send her a message: “Tell her that I send her all my love. And that young people are going to do something.”

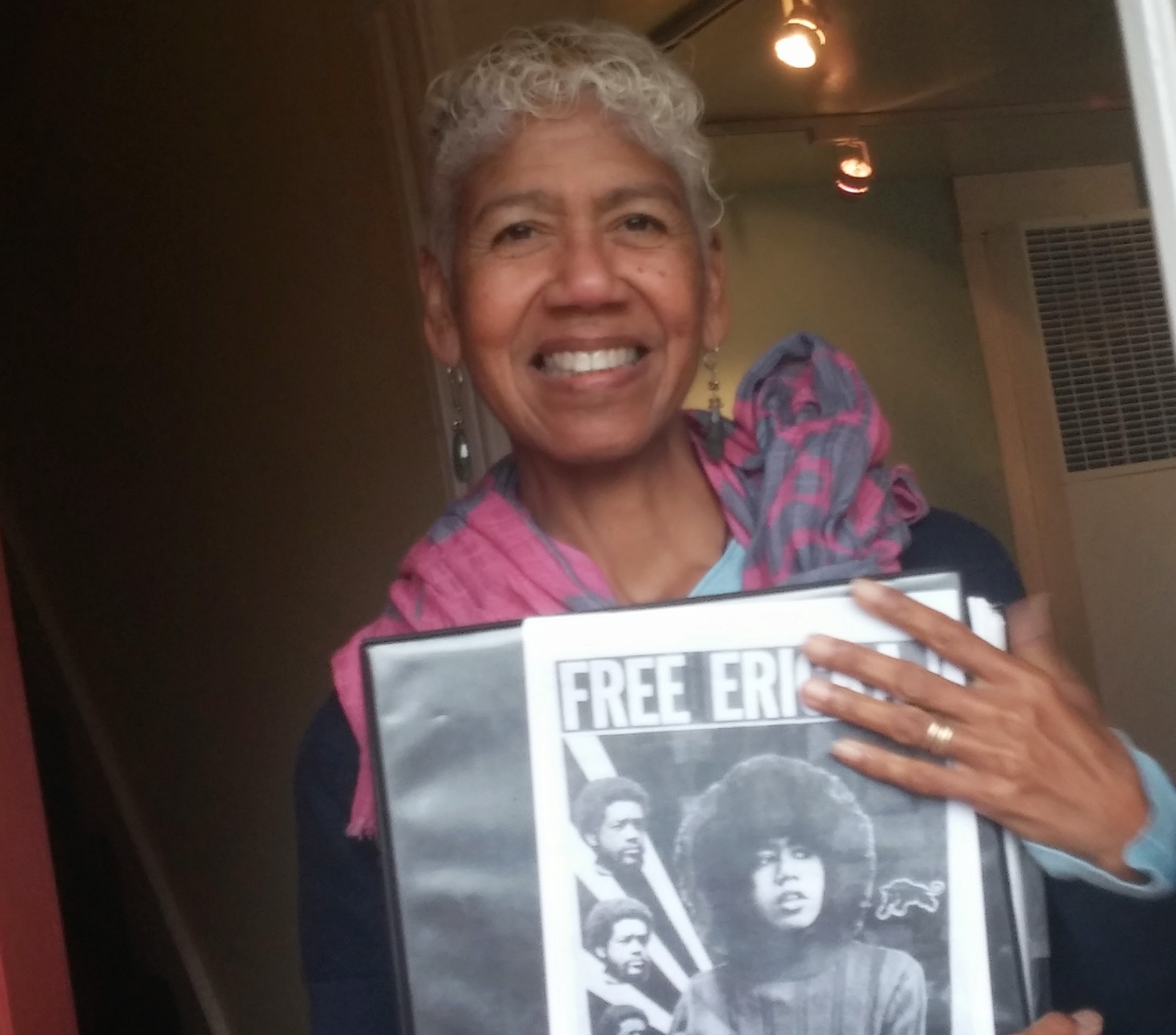

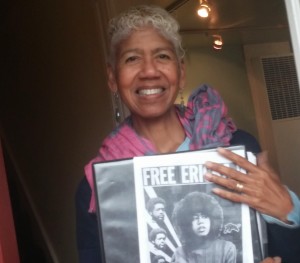

Ericka Huggins’ name may be familiar. She was a founding member of the Black Panther Party chapters in Los Angeles and New Haven, Connecticut. She was also director of the Oakland Community School, the forerunner of modern-day charter schools, from 1973-1981. She has lectured and traveled extensively, is a published poet, and was the first woman and person of color on the Alameda County Board of Education.

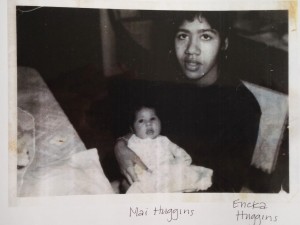

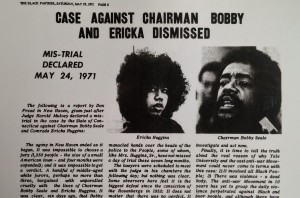

She was also widowed, at 19, when her husband was assassinated on the UCLA campus in 1969 by members of the US Organization, who were likely spurred on by an FBI agenda to fuel rivalry between US and the Black Panther Party (BPP). She traveled to her husband’s home in New Haven, Connecticut with her newborn daughter to bury him. There she started the New Haven chapter of the BPP, but was arrested and incarcerated on charges of conspiracy and murder along with party leader Bobby Seale. The resulting “New Haven Trial” was the longest to date in Connecticut history, sparking a public outcry across the country about the impossibility of a fair trial for the Panthers. Ultimately in 1971, the charges were dropped and the case was thrown out.

Huggins said so many of her students can identify with her experience, “because their parent was incarcerated, or they had gone through becoming an immediate single mom, or had been widowed themselves.” She maintains that in order to inspire students, one must be inspired by them as well. What do Huggins’ students teach her? “My students teach me connection. They’re fun, they’re funny, they’re fiery in a certain way, and they’re compassionate,” she said. Many of them live in East Oakland, in the same communities where Huggins has lived and worked for decades. It’s clear that she treasures this connection with all her students, neighbors, and allies.

She also happens to share a fence with me. I know her as a neighbor who, along with her partner, has slowly been renovating an old Victorian property with a new water-friendly garden, the pride of which is a bamboo tree just outside her pantry window. I visited her home on a rainy day in December, where she made us a pot of chai tea. Her living room is filled with comfortable chairs and neat stacks of books on subjects ranging from activism to poetry. One shelf holds a small framed picture of Huggins on a podium with President Barack Obama.

As we talked, our conversation turned to current events such as the Ferguson aftermath and the seemingly endless string of police shootings. Both former and current students contacted Huggins– she told me many sent her text messages from far corners of the country, asking “what can we do?” and she would shoot back: “do something, even if it’s just spit”, quoting a line written by her friend Bunchy Carter. She wants to teach those who seek her guidance to work towards a movement that is sustained, not a movement born of crisis. She explains “it’s not a reaction, but a response.”

“It’s systemic,” she said, referring to the power structures in America that are built out of institutional racism. “If I had skin cancer, would you tell me to put a band-aid on it? No. So how can this systemic illness be changed if we all don’t think about speaking up?” she asked. In the case of the Michael Brown shooting, she spoke of the officer, Darren Wilson, acting “literally the way St. Louis expected him to, by law But we always look at systems rather than persons when we’re trying to change.”

Activism runs strong in Huggins’ DNA, but with a personal and political history that could undo even the strongest-willed person, she is notably grounded and centered. The key, she said, is meditation, a practice she taught herself while imprisoned. “Meditation helps me take a pause so I can be strong enough to meet whatever is there. Be equal to. Not less than, not more than, feeling inferior or superior to the moment. I’m equal to that moment.”

Huggins taught meditation to her students throughout her career. One student from Oakland Community School came up to her 40 years later and said “Thank you so much for teaching me the tree pose.” She pointed to this example to show that teaching and service to others has “an exponential life in the distance.”

One of her students remembers the Oakland Community School. He didn’t attend, but he remembers how the school and the BPP were always doing something for the community, from the free breakfast program to clothing drives. “Oh, we all knew Miss Huggins there!” he recalled. He feels that then and now, Huggins presses the concept of service to the community.

Oakland Community School took a different approach to helping children, and that approach is something that Huggins would like to see in present day school reform. “It was tuition free, student-centered, community- based,” she explained. “Three meals a day, and the best people you could find anywhere. And it was a precursor to charter schools in terms of it’s principals. But we weren’t teaching money. If the money was funny, too many strings, we’d say, ‘No thank you, bye!’ And if a teacher came in wanting to employ antique tactics of educating and punishment? No. We had no detention, nothing like that. They had already had enough detention.”

Huggins was the first woman and first person of color to be on the Alameda County Board of Education in 1976. She was appointed by then State Assemblyman Tom Bates, currently the mayor of Berkeley. “He said, ‘Ericka, this is a bunch of old white men. We got to do something.” The Alameda Country School Board served 19 cities at the time. One of the tasks of the board was to preside over hearings for children with special needs, or as she says: “children with different learning styles or ways of navigating the world.”

Huggins quietly changed the way the Alameda County Board of Education interacted with the families who showed up to hearings about truancy or behavior issues. She would simply ask the mothers, “How are you doing today?”

“You could just see their shoulders relax,” she said. ” And when I asked them what was going on, they would give me a completely different story than the teacher or the principal who expelled them gave the board of education.”

It is this dialog, this way of interweaving the personal and political, that is the hallmark of Huggins’ work.

Back in the classroom at Merritt College, a student reminds Huggins she promised to tell the “ATM story”.

Huggins takes a moment, and begins telling the students of meeting a woman at an ATM in Hayward in 2011. The woman (who she calls Jane Smith) recognized Huggins, and asked to tell her something privately in her van. Smith told Huggins she was there on the UCLA campus, January 17, 1969, when Ericka’s friend Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter and her husband, John Huggins, were assassinated. Smith talked about how the men laughed and joked with her between classes that day, and how frightened she was when she heard the gunshots ring out. She never told her story to investigators, because she was afraid of the trouble it would bring.

Huggins remembers sitting in the van, listening to this woman, a stranger, answer so many questions she had about that tragic day, four decades earlier.

The classroom falls silent as the students take the story in. “It just goes to show you that if you’re seeking answers, if you’re seeking closure to something, life isn’t over yet. There’s still time,” she says.

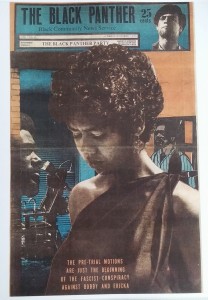

All images courtesy Ericka Huggins’ personal collection

Sara is a proud resident of the Clinton/East Lake area of Oakland, where she enjoys her current gig as a stay-at-home mom. She grew up in Minnesota and Colorado before moving to the Bay Area in 2006. She has a background in art and worked as a graphic designer for many years. She feels her connection to the community is best held by exploring new places, asking people about their stories, and bearing witness to the changes surrounding us all.

Hi Sara,

I don’t know if this communication channel is still operative, but will try it anyway.

I heard Ericka yesterday on a replay of her Bioneers speech in 2017 and was touched by her story, bits of which i have heard over many years.

I would like to send her a copy of the book i released last year which touches on the impact the Black Panthers work made on me.

Might it be possible to get it to her through you?

Thanks for a wonderful, insightful article on a powerful woman, and for any help you might provide me in connecting with her.

Susan Raycraft

Thank you!

Insightful article!! Where ish she and what is she dOin’??

Great article Sara, keep up the good work

” Power to the people” to quote the BPP!

Very insightful, it takes the reader on a mini tour of the 60’s the good, bad and beautiful.