By Edward Cervantes

Oakland Pride was creeping up and I had no plans to attend. Since coming out over a decade ago, I had been to 2 or 3 Gay Pride festivals every summer. But this summer, for the first time in my adult life, I would not make it to a single Pride event. The excitement I felt at my first, during the summer after my sopho

more year of college, was replaced with questions about Pride’s relevance.Wherever I was living and with whomever I was close to at the time, Pride plans were made far in advance. Outfit, transportation, after party, and crash pad were all pre-arranged. It was ritual – an opportunity to bond.

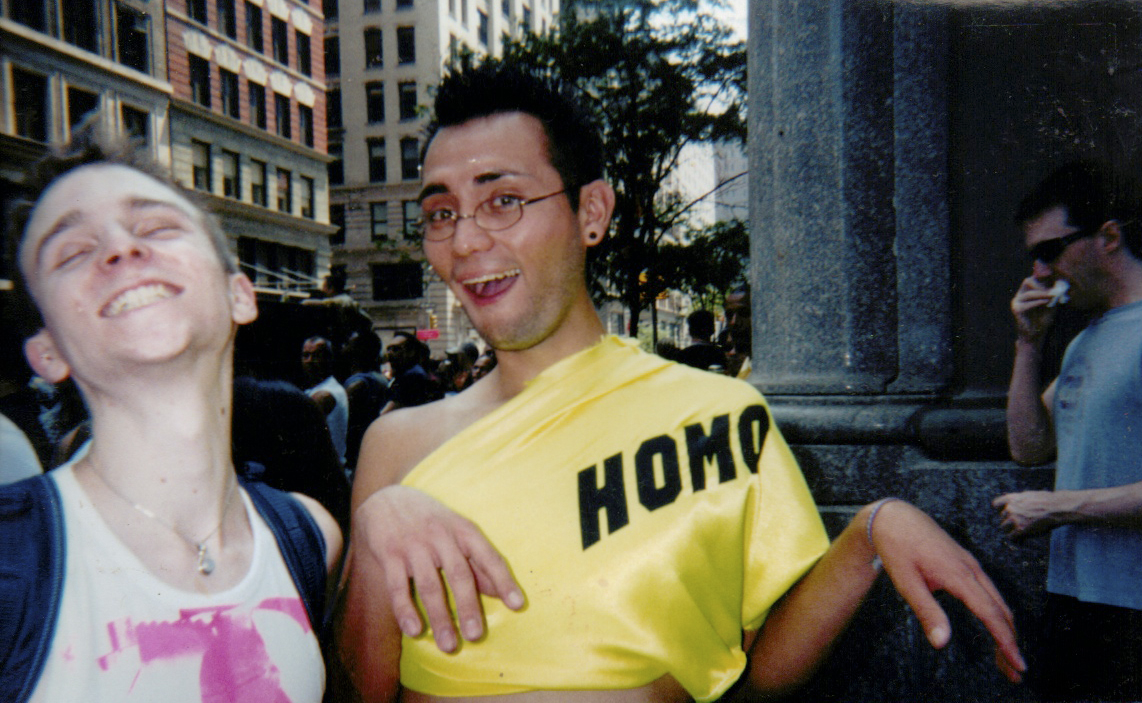

Pride never failed to make me feel connected to or proud to be part of the LGBT community. I liked the outrageousness, the heightened sexuality, the humor, the drinking, the dancing, the debauchery, and most of all, the shameless expressions of self. For my first Pride, I fashioned a top out of a neon-yellow piece of fabric screen-printed with the word “HOMO” in bold caps. People on the street laughed, took pictures, commented positively, or made rude remarks. I overheard one gay man cattily say to a friend about me, “look at her, she thinks she’s so cute.”Then he came over to me and pointing at the four letters angled across my chest said, “that’s not OK, you should be ashamed.”

But I wasn’t ashamed. That was the point. I was a proud homo. Gay. Queer. A fag. Whatever it was called, I was proud.

I loved the attention and saw value in causing discomfort in others with flamboyant, over-the-top displays of homoness. From then on, I did it as often as possible. Lashes, tall mohawks, eye shadow, dangly 80’s earrings, manicured nails, shoulder-pads, leggings, heels, sashay: I sought to shock. It was fun, but the goal of “queering spaces” with loud outfits and flaming behavior was to stretch the boundaries of acceptability.

Pride was when more of us felt comfortable taking our full gayness to the streets and has served a similar function: marching through the streets in our Sunday gayest made it easier to be our daily, ordinary gay selves at the office on Monday.

But every year, Pride gets less bold, less brazen. And from attending the last two Oakland Prides, it seemed to me to be stripped of almost all overt gayness. The Oakland Pride website boasts, “our family focused programming embraces a diverse community that has resulted in the most positive celebration.” Indeed, organizers succeeded in drawing a diverse group of celebrants to this year’s festival.

But it might as well have been Art and Soul Oakland. Perhaps a merger should be considered. To simplify, Pride could simply be a stage at Art and Soul – which would also serve to display our pride to a wider audience. Our straight friends could see how proud we are to be gay.

Reluctantly, I decided to attend Oakland’s pride festival for a third time. But this go round, I was on a information-gathering mission. Were my worst fears true – were gays getting less openly, outrageously, fabulously gay? Had the desire for mainstream acceptance and marriage rights made our community unrecognizably normal? Or was Oakland onto something new – was our city’s Pride festival a sign of an exciting “family focused” trend?

I asked Marsha Martin, director of Get Screened Oakland, an organization seeking to provide HIV testing to all residents, about the significance of Pride and she also pointed to the diversity and civic pride being displayed. “Anytime you get people out in such large numbers, enjoying the sunlight and feeling good about themselves, you have a community that feels better about itself,” she explained. “That’s what’s important.”

Compared to the pride festival on the other side of the bay, what was different about Oakland Pride? “Less naked people,” said three 16-year-old friends almost in unison.

Already veterans of the pride circuit, Truman, Sue and Kerry were unchaperoned and looked forward “just to dancing and having a good time.”

Others also commented on the relative modesty of the event. Sabrina, 28, said she preferred Oakland Pride for that reason.

She explained that some of the behavior common at other pride festivals was partly to blame for discrimination against the LGBT community. “Personally, I don’t want to see naked people, gay or not,” she said, “and just because we are gay doesn’t mean we are like that.”

Finally, somebody had put words to what I had been sensing at the festival and in the gay community more generally.

I can’t argue that Oakland Pride was a shining example of diversity. And I agree with Marsha Martin’s assessment that the time spent outdoors enjoying perfect weather and the overall positivity of the festival could only be good for Oakland.

But do we really want Pride to be about how “normal” and acceptable we could be? Do we want what was first envisioned as a commemoration of the Stonewall riots – an uprising of “deviants” tired of police abuse and unwarranted arrest – to now be about showing the world that we can form families that look just like heterosexual families but with two mommies or two daddies instead?

To me, Pride has always been a celebration of our status as sexual outsiders. By being outrageous, gender-fluid, kinky, and obscene, we hoped to change society and make it more accepting of gender and sexual variance – work that is far from over. Now more than ever, we need to shock, disgust, inspire, and teach. Including within our own community.

The LGBT rights movement is now equated with gay marriage, the ultimate goal being acceptance of our relationships as “normal.” I fear that with each victory, the LGBT movement will loose a little more of its edge and increasingly turn against those that fall outside the new norm.

I wonder if those of us who aren’t normal, who don’t want relationships modeled on heterosexual ideals, and who have no interest in raising children will be left behind by the acceptable, almost-straight-except-for-their-private-bedroom-behavior gays. If Gay Pride is for “acceptable,” family-focused gays, then perhaps it’s time for a new kind of pride parade. A Freak Pride Parade?

I do agree with the LGBT movement’s message that nobody is defined by their sex lives. Being a freak is about much more than being gay. It’s about daring to be different, to live your own truth, to be bold and shameless, to be exactly who you are regardless of society’s ideas of appropriateness.

A freak prefers to be crass, to shock, to cause discomfort.

I know I’m not the only or the biggest freak in Oakland, so in the words of a freak from the 90’s, Adina Howard, let me put a call out to my fellow freaks:

Let me lay it on the line

I got a little freakiness inside

And you know that the man

Has got to deal with it

I don’t care what they say

I’m not about to pay nobody’s way

‘Cause it’s all about the dog in me

Mm-hmm.

A native Angeleno and former New Yorker, Edward Cervantes is proud to now be a resident of Oakland, where he lives with his partner Jim and their three cats. He is a candidate for a master’s degree in public policy at Mills College. Fascinated by Oakland’s history, diversity, and geography, Edward looks forward to further exploring and writing about the city’s richness and complexity.

Be the first to comment