Throughout most of the past decade, Azlinah Tambu had been active as a parent at Parker K-8 school in East Oakland. She always participated in the bake sales and resource giveaways held on the campus of the public school that her two children used to attend. “I gave that my all,” Tambu told Oakland Voices about her involvement.

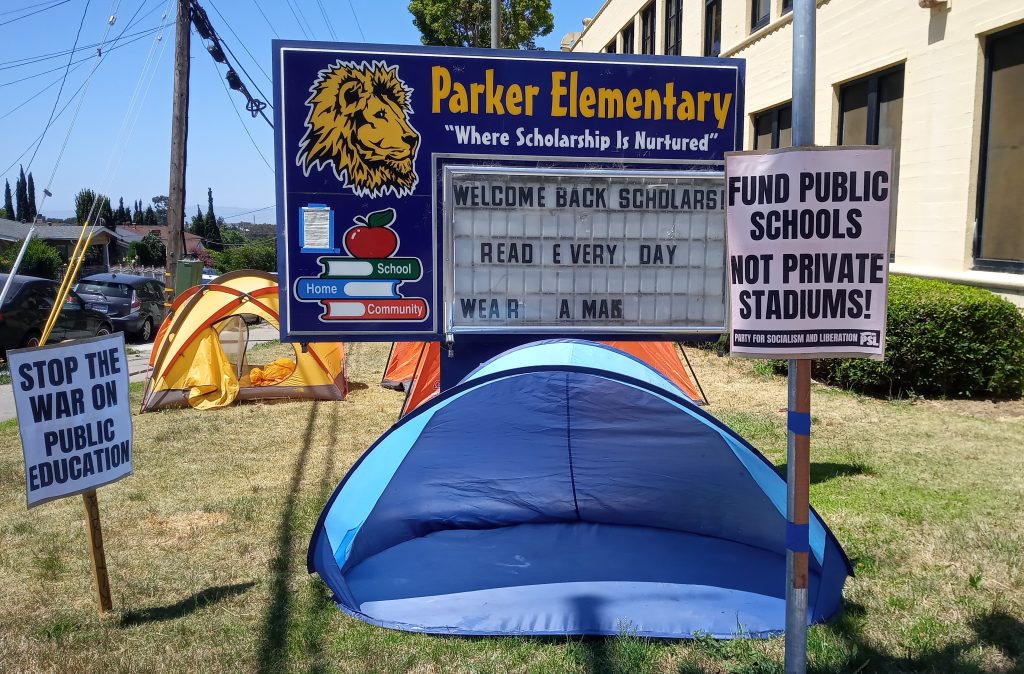

Parker K-8 is one of the schools that the Oakland Unified school board closed last year in a move, supposedly to save money. On the last day of the school year, after the graduation ceremony, several Parker families simply didn’t leave the building, spending the night in the auditorium. Other activists from the community joined those parents to occupy the school in a form of protest against school closures, dubbing the direct action “Parker Liberation.”

On October 2, 2022, this four-month-long protest against closures and the broader privatization of education in Oakland officially ended. In the final hours of the Parker Liberation, occupiers cleaned the building and helped former Parker families and staff retrieve personal items. “Over the summer, the Parker Liberation provided educational programming, nutritious meals, and activities to students who were at risk of losing the only public elementary and middle school in their neighborhood,” activists posted in an official statement. “For these kids, school closures remain a very personal and troubling act of violence devastating their ability to thrive in an increasingly gentrified city.”

“A Safe Space”

The Parker campus is located in an East Oakland neighborhood where violence has historically been so ubiquitous that it is nicknamed “The Killing Fields.”

When the protest occupation began at the end of May, the school building was a mess with supplies, equipment and books piled up along the hallways and in the auditorium. In the 130 days in between, Parker Liberation activists cleaned and maintained the building, hosted a free summer school program, organized community food and gift card giveaways, distributed water and snacks to families daily, and even defended the building against attempted infiltrations by feral cats.

Parker activists organized spoken word open mic events, political discussion groups, community barbecues, book club meetings, flag football tournaments, and pickup basketball games.

“From the day it started to the day it ended, we had the time of our life,” Tambu said. “We had a safe space, we had fun, we learned so much, we went on field trips, we provided structure, we taught our kids to cook, and we provided meals.”

She added that of the 20-25 kids who participated in the summer school program, all of whom were former Parker students, most willingly showed up to school board meetings as well. “I think they’ll never forget,” Tambu said. “It was the best summer of our lives.”

“It is strongly advised that you do not go into the building.”

While violence is plaguing the Oakland community, including some public school campuses throughout the city, only one incident of violence occurred on the Parker campus throughout the duration of the occupation. That was on August 4, 2022.

According to public records acquired by Oakland Voices from the City of Oakland, someone from OUSD headquarters sent an armed private security detail to “detain” three activists who were at the school.

Those 911 call logs and audio recordings prove that OUSD Chief Governance Officer Josh Daniels placed at least four separate calls to 911 on August 4, sounding increasingly panicked in each one.

In a city experiencing triple-digit homicides for the third year in a row, Daniels placed his first call to 911 specifically to ask when police would investigate a report of motion detectors being set off in a school building where activists had been holding a peaceful protest for the previous two months.

In his subsequent phone calls, Daniels never told the 911 operators that the security contractors with whom he was coordinating had detained an individual inside the building, and that that was the reason why the situation had escalated.

After Daniels’ first call, someone named James Long called 911 identifying himself as “Head of OUSD Security.” Long informed the 911 operator that, “We are about to detain some individuals at Parker Elementary School.” District spokesperson John Sasaki declined to confirm whether or not Long is employed by the district.

Long acknowledged that he believed that the three adult Caucasians (two females and one male) seen on video at the school were unarmed. When the 911 operator asked him if his team was armed, he replied, “We have firearms permits, but we don’t have them on our possession.”

The 911 operator advised him and his team not to go into the building, which lead to the following excerpted exchange:

Long: “But if they do have weapons, you know, we are prepared to go back to our vehicles and arm up.”

911 Operator: “I’m sorry, what did you say, sir?”

Long: “If they do have weapons, we’ll stand down.”

911 Operator: “Ok, so I can’t advise that it’s safe for you to go into the building. So, I have the call in for officers, and let them know that…you know…that these individuals are in there, but I wouldn’t advise that you guys go into the building.”

Long: “Ok, duly noted.”

911 Operator: “I can’t tell you what to do, but it’s strongly…not (inaudible)”

Long: “It’s on record that you advised us, so I appreciate that.”

911 Operator: “Ok, yeah, for your own safety, you should wait for officers.”

In all, the 911 operator advised Long six different times not to enter the building, including at the end of the call when she reiterated, “Again, it is strongly advised that you do not go into the building.”

However, a little more than an hour later, Long called 911 again, this time from inside the school building. Sounding out of breath, he was calling to request an “expedited” police response. He claimed that someone “bum rushed the door” and “physically assaulted the person on the door,” and his security team had detained that individual. In the background of the recording, a voice that is likely Max Orozco, the person who was being detained at the time, can be heard questioning Long’s narrative.

A video posted online by local journalist Jaime Omar Yassin shows Orozco walking into the building, and then Orozco can be seen talking to the security contractors once inside. Orozco ended up requiring medical attention for multiple injuries, and he claims that he was thrown to the floor, handcuffed, and multiple security contractors kneed on top of him. According to Orozco, one member of the security team put her knee on his neck while he was face down on the ground in handcuffs and restrained by multiple other security contractors.

Another Parker activist, Rebecca Ruiz, suffered a concussion when thrown headfirst into a tile wall by one of the security contractors. Several other Parker activists suffered various other injuries as well.

Attorney Walter Riley is preparing to file a lawsuit against the district on behalf of the Parker activists injured during the August 4 incident. Regarding the decision to send the private security detail to Parker and the conduct of the security detail that day, Riley told Oakland Voices, “It appears to be outrageous and totally uncalled for given the summer of acceptance and tolerance of the occupation and the fact that there were negotiations ongoing at that time.”

The “negotiations” Riley is referring to are the discussions between Parker activists and OUSD representatives that ultimately led to the end of the Parker Liberation.

The private security company involved in the August 4 incident, Overall and Associates, was originally contracted by the district last spring to provide security at sporting events, graduation ceremonies, and board meetings. Their contract with the district expired in June, and they have not been present at any board meetings so far this school year.

In another video posted by Yassin, the security contractors refuse to identify themselves, and instead tell Yassin, “John Sasaki is the one who will handle all questions.” Sasaki declined to answer the question of who decided to send the private security detail to Parker that day, but Sasaki does not have the authority to hire private security contractors, and he told Oakland Voices that he “had no role in that assignment.” He also told Oakland Voices, “OUSD did not instruct the security company to bring firearms with them to Parker, and as far as we know, they did not bring firearms to the campus.” However, the 911 audio tapes reveal that the contractors did bring firearms with them that day, even if they left them in their vehicles.

The August 4 incident ended when Oakland Police arrived, freed Orozco, and escorted him and the security team out a back exit. Orozco was given medical care and was not charged with any offense.

The incident bolstered community support for the liberation, which had been waning after the summer school program ended the week prior to August 4. It completely dominated public discussion during the first school board meeting of the year.

According to Parker Liberation activists, four OUSD educators have lost their jobs after participating in the Parker protest. Parker activists have demanded that those educators get their jobs back and that no other activists be retaliated against for participating in the protest. District leaders have not committed to either demand.

The Future of Parker School Building

As for the future of the school site, acting Superintendent Sondra Aguilera introduced a resolution at the October 6 Board meeting to use the former Parker school campus for adult education and community programs. The resolution passed by a 4-2 vote.

While some activists say that they still wish that the school could serve neighborhood kids as an elementary or middle school, they can live with the compromise. Tambu, the mom who has been active all along, said “It’s whatever,” about the school board’s resolution. Tambu’s children now attend schools that are two miles away from Parker. She says that there are several former Parker teachers at one of the schools, and the staff in general are great at both schools. However, the travel to and from the new schools is difficult, so she drives other former Parker students to those schools in addition to her own children. She expressed a sense of relief that the former Parker campus is not currently slated to become a charter school or condominiums. “It’s not what I set out for, but I’m not mad about it.”

Tony Daquipa is a dad, essential bureaucrat, photographer, urban cyclist, union thug, wannabe stonemason, karaoke diva, grumpy old man, storyteller, and preserver of history.

1 Trackback / Pingback