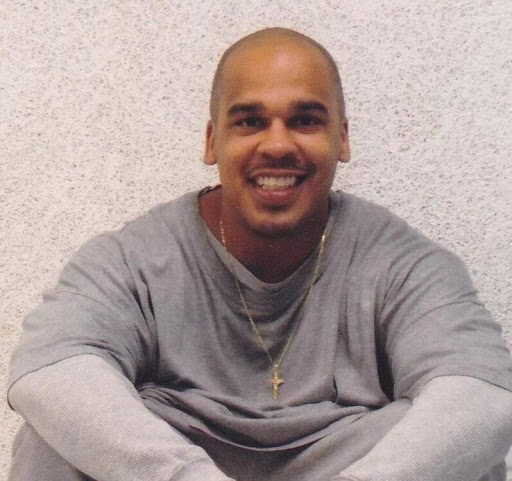

Accomplished writer. Incarcerated person. These are some of the descriptions one could use to describe Jermon Clark, 42.

“If I would’ve had a stable household as a child and parents that showed an interest in me or my talents, I would’ve ended up differently,” wrote Jermon Clark, now 42, in his 27th year serving time for a carjacking turned deadly, when he was 15. Originally from Oakland, Clark’s life was impacted by an almost textbook case of the intersection of disastrous circumstances, from a heroin-addicted single mother, who had turned to prostitution to support her both her habit and her seven children, to being shuttled through multiple foster homes and, finally, when he was 14, Child Protective Services moving him to Texas.

“I’ll Never Be Normal” is the title of Jermon Clark’s unpublished autobiography, which he began writing after being incarcerated for being an accomplice to a carjacking turned deadly when he was 15.

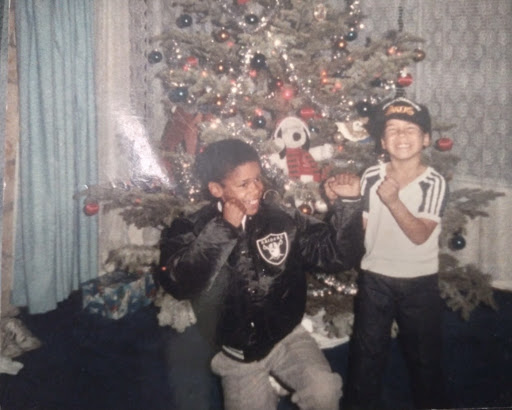

Growing up, Clark’s father was abusive and mostly absent, and he entered the foster care system as a teenager. He was later sent to live with his father, against his will, in Texas. It was the first time he had ever met, much less lived, with his biological father. “I had no really close friends,” Clark said in an interview. “When you go through the stuff that I went through, you become ashamed of the things you went through, you don’t want to make yourself look different. I never really opened up and told anyone, because how many kids my age had seen their mothers do drugs and be a prostitute? It brought out a lot of anger issues.”

His crime had started out with the intention to steal a car to drive to California from Texas, where Clark and his two abettors were intending to go. Clark was the driver, with an understanding that the owner of the car, a teenage girl known to two of the guys, would be abandoned in a remote spot, intending to give the three of them time to make their getaway on a cold Thanksgiving Day eve in 1993. Clark waited in the driver’s seat as the young girl was pushed out of the car but did not expect one of the guys to attempt to shoot her, but when the gun jammed, beat her to death with it instead. As they attempted to make a quick getaway, after first stealing some gas from a gas station, where you could pump before you pay, they were pursued onto the highway by the police, and finally crashed the car after speeding on the icy road. It became clear the car was stolen and the three young men were taken into custody. Clark was eventually sentenced to 50 years in custody as an accomplice, though he states he did not know of or actively participate in the murder. Clark is serving his 27th year now.

The victim’s mother wrote to Clark that “She had forgiven me and she knows that her daughter did, too. She tried to visit me five years after the crime.” However, she was not able to due to the prohibition of visitation by the Victims’ Impact Program. “She forgave me because she was a woman of faith and knew that my role was minimal,” Clark added that they corresponded for several years after that but then she stopped writing because “I told her I was working on my case. She believed six years wasn’t enough time for me to do for the role I played in the crime. She believed I should at least serve 15 years of my sentence.” She passed away in 2012 without them having met.

While incarcerated, Clark has had opportunities to complete his high school diploma, further his education, and participate in a variety of programs. He completed his G.E.D. in 1996 at a federal juvenile facility, and a decade later got his Associate’s Degree in Social & Behavioral Science from Coastline College, which, he notes, “which has given me an understanding of myself and the system and why people do the things that they do. I was able to understand the dynamics the way that different systems influence people to do things that do,” adding, “I look toward science as well. A personal’s frontal lobe is not fully developed until the age of 25, you may not fully understand the consequences. It took me a long time to accept that my actions did hurt a lot of people.”

He was in the START program, “Start Taking Another Route Today,” until it was cancelled. The START program allowed inmates to speak to at-risk youth in the community. “If your story is appropriate to relate to somebody else, you can tell it, they don’t give any points. Some kids who have already had a bit of a brush with the law. I know I made a difference. In a few instances that my story affected them, any time you can take a negative and make a positive, that makes me feel good.” Later, Clark also was a Suicide Watch Companion for eight years, until the program was discontinued. As a Suicide Watch Companion, inmates are assigned to work with fellow inmates identified as at risk of committing suicide. They spend several hours per day, observing behavior and talking with the identified inmates.

One of the more surprising aspects from incarceration was Clark’s discovery of writing. Today, he is published as part of Pen America, an organization whose mission is self-described as “defending free expression, supporting persecuted writers and promoting literary culture.”

Clark explains that did not write much as a child, just letters. He began writing after 12 years of incarceration, when he was working in a medical hospital, and was encouraged by a staff member, Consuelo Johar, to tell his story. After an institutional infraction remanded him to “the hole,” or solitary confinement, for three months, he started his autobiography, “I’ll Never Be Normal,” finding it helped pass the time, initially writing it out by hand on a legal pad. While still unfinished since 2013, Clark notes he would update it if a publishing opportunity becomes available.

Clark learned from another inmate about Pen America, where his essay, “Voice of an Unheard Nation,” won the Honorable Mention in 2010.

An excerpt from the essay is below:

A lot of American citizens have a misinterpretation of prisoners. Society says, “If you know one of them, then you know them all.” This way of thinking could be no further from the truth. I am not going to go “pro—prisoner” and tell you that all men behind these walls are good, because if I did, I would be lying to you as well as to myself. I will, however, tell you this: people do have the God-given ability to recognize their mistakes, to learn from them, and to change.

His author’s page on Pen America notes, “Writing has enabled me to heal old wounds, find serenity in dealing with my situation, has ignited the fire in me to self-actualize, and at the same time helped me discover a hidden talent that impels me to walk down paths of righteousness regardless of my circumstances.” He has written about the pleasure he and his fellow prisoners felt about Barack Obama’s election such as the one linked above, and other personal stories.

Clark says that writing has helped him to heal and to also come to an understanding of his role in the crime, “without doubt.” Reflecting on what led a young person to commit violent crime, he said, “Sometimes it’s hard to think about the consequences. I’m sympathetic and empathetic; I’ve lost people in my life, but it might be the only thing his mind can come up with, he may not think of the consequences that may lay on the other side of his actions.”

He hopes to make a contribution to society when he gets out of prison, noting, “I believe that I could be a benefit to others that are on the path that led me to prison. That being said, I know I can be a help to society by steering the youth in a different direction. I’ve obtained the tools to properly channel my message to the youth while in prison.”

Clark considers the options after his possible release. “I want to get out and do the right thing: get me a job, get stable, where I can provide for a possible family.” He says he hopes to get a job like a truck driver or at the oil refinery.

Thinking ahead, Clark is reflective. “One thing, coming out of prison, set your sights on something that would be attainable. I know release will be a struggle, so I will be prepared, eager to learn everything that I can to succeed, assisting people getting out of prison. I would like to live in California.”

Clark believes that in sharing his story and his writings, that it might help others. “I perfected my writing, although there are still a lot of flaws in my writing. I let a lot of people read it. It gave me confidence. I know my writing needs a lot of work, but if I can share my story, someone might make a different choice. If I could get out and be an activist, I could make a difference in a whole lotta lives.”

Some of Jermon Clark’s Writings:

My First Day in Prison/Prison Writers

Editor’s Note: We changed the original title and first sentence, which included the description “convicted felon.” While accurate, we realize the weight of words that may follow someone permanently. To learn more about this discussion, visit the Marshall Project.

Debora Gordon is a writer, artist, educator and non-violence activist. She has been living in Oakland since 1991, moving here to become a teacher in the Oakland Unified School District. In all of these roles, Debora is interested in developing a life of the mind. “As a mere human living in these simultaneously thrilling and troubled times,” Debora says, “I try to tread lightly, live thoughtfully, teach peace, and not take myself too seriously.”

My East Texas (Sunny South) childhood friend whom I have always called “lil brother”, Jermon, I am so proud of you. Reading this brought tears to my eyes. Even tho we were literally kids back then, I will always remember U being one of the sweetest kids I knew. Always smiling and making somebody laugh. Until I read this story, I never would’ve known or even guessed u had been through so much. My prayer for you is that you will be able to get home soon and keep your promise, to continue to let your story be a testimony and help another young man who may be headed down the wrong road, make a different choice in life. You definitely have a story to tell. Continue to be that blessing to someone & share this. I am super proud of u and my continued prayers for strength and healing for u everyday.. Your dad would be so proud right now.. I know he is!! And I am too “Lil Brother”… Keep writing!! Don’t ever give up.. Much luv always.. (as I ALWAYS say)❤️

Its incredible the way time can change a boy into a man .everyone is capable of making change . Everyone deserves to be reevaluated and released based on the change god is good your time will come .keep in the light and walk by faith in jesus name.

This was an awesome read. Jermon is such an awesome guy, and I know, given the opportunity to be released he would definitely right his wrongs & be such a positive force in his community. Thank you for sharing his story! Not only am I rooting for him, but I’m continually praying for him!

Like so many of us that have been incarcerated for our past circumstances. I pray his story helps others and he is released from the belly of the beast

Thank for sharing Jermon’s story. He is right about you need parent support early in your life.