One of the activities Teresa Williams remembers as a student at the Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School was a field trip to the Oakland Airport. The students entered a vacant plane where they were encouraged to dream and envision where they would like to go someday.

“Though we didn’t have any money, I sat on the plane and saw myself flying all over,” Williams said. “Now, I’m a teacher who has traveled to many places, including several countries in Africa.”

Growing up Panther

Teresa D. Williams’ parents, Louis Randolph and Mary Williams joined the Black Panther Party in its formative years. They entrusted the Party with their children’s upbringing as they labored for the cause. While she and her siblings received a good education and had outstanding teachers, the experience was often bittersweet.

Williams, the third of six children, was a toddler when her parents joined the Panthers in 1966. Her father was a foot soldier in the Party. Mary Nell Williams was one of the primary cooks at the Lamp Post, a restaurant the Black Panthers regularly frequented.

As their mother worked at the restaurant, Williams and her siblings spent countless days away from their parents. They lived in a communal setting with other children and surrogate mothers. Weeks would pass before the Williams’ children saw their parents.

Her paternal grandparents were concerned about the children’s time at the facility. This conflict with her parents led to her losing contact with her grandparents.

Williams felt abandoned and isolated. Her father was fine with it. He believed commitment to civil rights and involvement in the Party was justified.

Louis Randolph Williams and post-traumatic stress

Louis Williams served in the Vietnam War. He fought for his country and saw the Party as an opportunity to fight for Black people’s civil rights. As a Black Panther armaments officer and gunsmith, he and his brother, Landon Williams, were out on the forefront and involved in violent confrontations with law enforcement. Police jailed the brothers many times. Her father served a fifteen-year sentence Louis served for an attempted murder for an ambush of an Oakland Police wagon in April 1970.

“My dad had post-traumatic stress from both Vietnam and prison,” Williams said. When got out of prison, he continued using drugs and drinking, she said.

Her uncle, Landon Williams, later drew upon the lessons he learned as a member of the Black Panther Party and dedicated his efforts to working with housing projects in West Oakland.

Mary Williams disillusionment and leaving the Party

Williams said her mother married young. She struggled to maintain her marriage, despite Williams’ consistent infidelities and absences from the family. She endured years of physical abuse and bitterness. During one of her husband’s prison stints, Mary Williams filed for divorce and left the Party. She continued to rely on the Party for childcare for the six children, though the children no longer lived communally.

“We received all three meals every day, were picked up at 6:00 pm,” Williams said. “Then we would go home, go to sleep and start the same thing over the next day.”

Much of Mary Williams’ disillusionment with the Party came from her perception of what she saw were hierarchies within the party. In her mind, there was colorism which favored the lighter skinned women for positions of power or leadership.

Some Black Panther Party members felt exploited

Additionally, Williams’s mother believed that the Party took advantage of them. She felt like the Party profited from her children’s images being used for advertising purposes. .

“The Panthers took thousands of pictures of us in the party, only to turn around and sell those pictures,” Williams said, “and we, the families, were never compensated. My mother was bitter over that.”

Oakland Voices could not verify whether any images of their family were sold commercially.

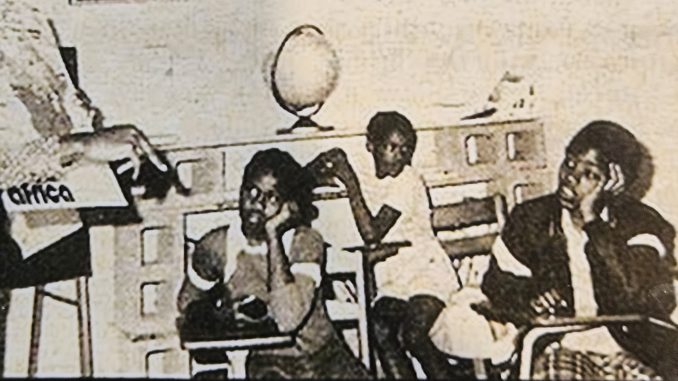

There are numerous pictures of Panther children at the Black Panther Party Museum in Downtown Oakland.

“Me and my sisters and brother are in those photos,” Williams said, referring to images of the Oakland Community School currently on display as part of “Each One, Teach One.“

The Black Panther Party Museum does license photographs, according to Dr. Xavier Buck, director of the museum. The images on display are by photographer Donald Cunningham.

School days at Oakland Community School

Though her mother had left the Party, Teresa and her siblings continued their education at the Oakland Community School at 6118 East 14th Street, now International Blvd. The Men of Valor Academy now uses the building.

Williams said there was always art around at the East Oakland school and another facility on East 14th near the Montgomery Ward building.. Artists and poet Ericka Huggins was the school director who advocated for the arts.

Williams appreciated poetry, but she was more into science.

“I was more geared towards the scientific part, but I can still write a poem, a pretty meaningful poem,” Williams said. “They were deep into art, poetry, and spirituality. I had really good teachers who guided me towards critical thinking components that have enhanced my teaching of my own students. I had what I learned years later in college, as dyslexia. The teachers told me I was going to be another Albert Einstein and do great things like him.”

‘My civil rights were taken from me with abuse’

She attended OCC through sixth grade, the highest level offered at the school. Williams believes the school taught meditation, art, journaling, and psychology to the children to address the trauma most of the children had endured at the school.

Williams alleged that some adults at the Oakland Community School abused children there.

“While my parents were fighting and marching for the civil rights movement, my civil rights were taken from me with abuse.”

Teresa D. Williams

“They sexually and physically abused us as children,” she said. “While my parents were fighting and marching for the civil rights movement, my civil rights were taken from me with abuse.”

Every single day, Williams felt abandoned.

When she transitioned to her neighborhood public middle school, she couldn’t concentrate on her studies. She still suffered from trauma, she said. Williams began cutting classes, staying home, or going to the library to read books and research science and math.

One day, on one of the rare occasions her father visited the family home, he caught her cutting school.

“He beat the crap out of me,” Williams said. “I ran to school through four lanes of traffic. That one time when my dad was being a father set me on the straight and narrow path to getting my life right.”

‘Each one, teach one’

For Williams, the teachings at the Panther school helped her cope with adversity and shaped her science curriculum and philosophy of “Each one, Teach on.” Today, Williams is Department Chair of Geology and Geography at both Merritt and Laney Community Colleges. She also volunteers as a geography instructor at the Contra Costa County Juvenile Hall system.

Although her time was not always happy, Wiliams’ is proud of her journey and the compassion instilled in her.

“That’s why I never really left Oakland. You can say all children have different experiences and those experiences make you who you are. It helped me become a teacher and to have a lot of compassion to help people.”

Teresa D. Williams

“That’s why I never really left Oakland,” Williams said. “You can say all children have different experiences and those experiences make you who you are. It helped me become a teacher and to have a lot of compassion to help people.”

As a child of Black Panther parents, Williams, 60, embraces being a “Panther Cub.”

“I like it. We are the children of the parents who fought for civil rights in the Black Panther Party,” Williams said.

Clarification: Dr. Xavier Buck, executive director of the Huey P. Newton Foundation and founding director of the Black Panther Party Museum responded to Oakland Voices after publication. According to Buck, “We do license images that we own in our archive, but oftentimes the photos are owned by the photographer. The photos in the Oakland Community School exhibit are from Donald Cunningham.”

Be the first to comment