El diablo sabe mas por viejo que por diablo.

The devil knows more from age than from being the devil

Fall, 2016:

The photo was taken from a low angle pointed upwards toward the shiny hubcaps of a 1960s VW Beetle that reflect an expansive courtyard as my father stands near the door in a perfectly tailored suit. He wears the confident smile of a comfortable, upper -class man in a country where such divisions are sharply upheld.

“That car was actually manufactured in Germany and sent to Bolivia,” he says. A hint of pride turns up the corners of his mouth and makes his eyes shine. The smile fades as he sinks backward on the couch, still in the reverie of days when he was most powerful. My parents lived in the intersections of Bolivia’s complicated history. They came of age in a time where adherence to certain behaviors and life choices was rigid; deviations were neither encouraged nor forgiven. We stand on the shoulders of giants. Except no one remembers the imperfections of the giants. The old, cinematic lighting of our memories fogs the details.

Summer, 1995:

The small, mountain church has an old, comforting wood smell. We sit down in the expectant quiet as my father remains standing in the front and begins singing Ave Maria, acapella. The sound of his voice fills the small church and I notice a new part of him. The part that wanted to become an opera singer. The part of him that honors God with song.

He rarely laughs with abandon though he enjoys telling jokes with an intellectual and cultural spin. He smiles, perhaps chuckles with mirth and carries a deep, kind sadness that’s been part of him for as long as I’ve been alive.

1940-1980:

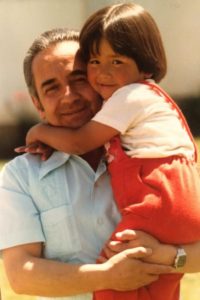

You (father) make your own kaleidoscope from broken glass on the street. You save your allowance for a month to rent a bicycle for an hour on Sunday. Despite humble family means and a widowed mother, your intellect and drive give you access to an elite, strict Jesuit education. The Spanish clergy teach you classical music as a pathway to God and this moves you, deeply. Yet familial expectations to become a civil engineer block your way. You meet this expectation quietly, without a fight. Beautifully composed photographs belie an unideal marriage. You exemplify Propriety. Respectability.

A small, slide-sized photo strip in an antique wooden frame shows a celebration. Confetti dots black windswept hair. The background open and raw. Andean. Remote. Your tailored, neatly patterned clothing against bright, geometric, Indigenous designs. Both garments are made of wool – one pressed and monochromatic; and one lumpy and chaotic from being woven and dyed by hands that follow different rules. Deep brown eyes squint in the bright sun.

Another black and white photo shows you at your desk with a picture of Richard Nixon lording above a neatly displayed American flag propped up in the corner. Framed photos of highway systems, bridges and roads that bear your design and connect cities across Bolivia’s vast plateau adorn the walls of your office. The United States’ Agency for International Development decides it will no longer fund Bolivian infrastructure. They offer you a choice: severance pay, or seven green cards with a pathway to citizenship in the U.S. for your family.

Winter, 1981

You cross an ocean, across time to land in a place that doesn’t fully welcome you or recognize the social stature you left behind. The seven of you, two parents and five children, are met by a blizzard that buries cars and cloisters people in their houses for days. You grapple negotiating a new beginning at your age. You live with distance and tension in a place where the culture and language are far from your own. You find a small group of people that somewhat look and sound like you. You play music with them and this brings you small moments of joy.

Summer, 1998:

We vacation in Copacabana–my maternal, ancestral homeland. The altitude and bus trip drain you. She smiles hatefully at you. You fight with her in your own, civilized way. You are unable to remember what brought you together. History holds us captive and the skies match the lake in their cold, high blue.

Winter 1999 to present:

You watch cancer ravage and destroy the life of your wife in a few short months after receiving a final letter where she says she’s never coming back. She comes back anyway, to die. You watch your grown children struggle through redefining their connections in her absence. Some are yet to be repaired.

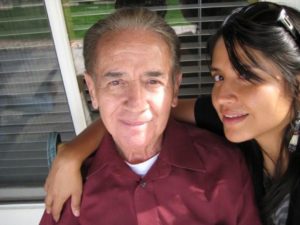

You sit in your silent, clean apartment. The memories accost you at dusk, into the night and you nearly break from regret. Always, the regret steals your dreams and you wake up empty. You wear solitude like a second skin. You have three cancers. Two in remission. The remaining one probably won’t kill you. You pass the time in a place with open skies and a dry wind. You don’t get much sun. You wear your past in the lines that frame your tired eyes. You still have a full head of hair and nice skin for being 85. Memories laced with regret weigh heavy on your slight frame and your breath is often short. You hang on.

We talk once a week, if not more. You always answer the phone. You always try to insert something positive through your anguish. You are reliable and generous. You have taught me how to approach things with a methodology. To be responsible, polite and on time. You loved me from the beginning. Before the beginning, even. And to have been so unwaveringly loved and supported are the reasons I walk tall and trust myself. You are the reason I believe I am deserving of love. I don’t know that I will experience that level of selflessness. I suspect it’s unique to being a parent, of which I am not. But you raised, supported and created five entire beings. Held together whole families across continents. You were in two places at once my whole life. For us, you abandoned your own history, culture, language, wealth and social standing.

My throat swells and I choke down a lump of ineffable gratitude. Words cannot adequately honor our connection or what I owe you, for you gave me the freedom to be myself. Thank you forever and beyond, until there is no more forever. And past that. To the other forever. Until I can hear again, all the songs you sing for God.

Sandra Tavel lives and works in East Oakland. Emigrating from La Paz, Bolivia and growing up in suburban Denver shaped her desire to put roots down in a place that is diverse, politically progressive and rich in social justice oriented history. This journey brought her to Oakland, which gets a disturbing and bizarre rap on much of the media that exists today. She’s looking to move the needle to create different narratives that reflect the complexity and nuances that make Oakland what it is.

She has been an avid writer and voracious reader her whole life. When she’s not working, reading or writing, you can find her at yoga class, hiking the Redwood Regional Park System or playing on the beach with her partner and two dogs.

Be the first to comment