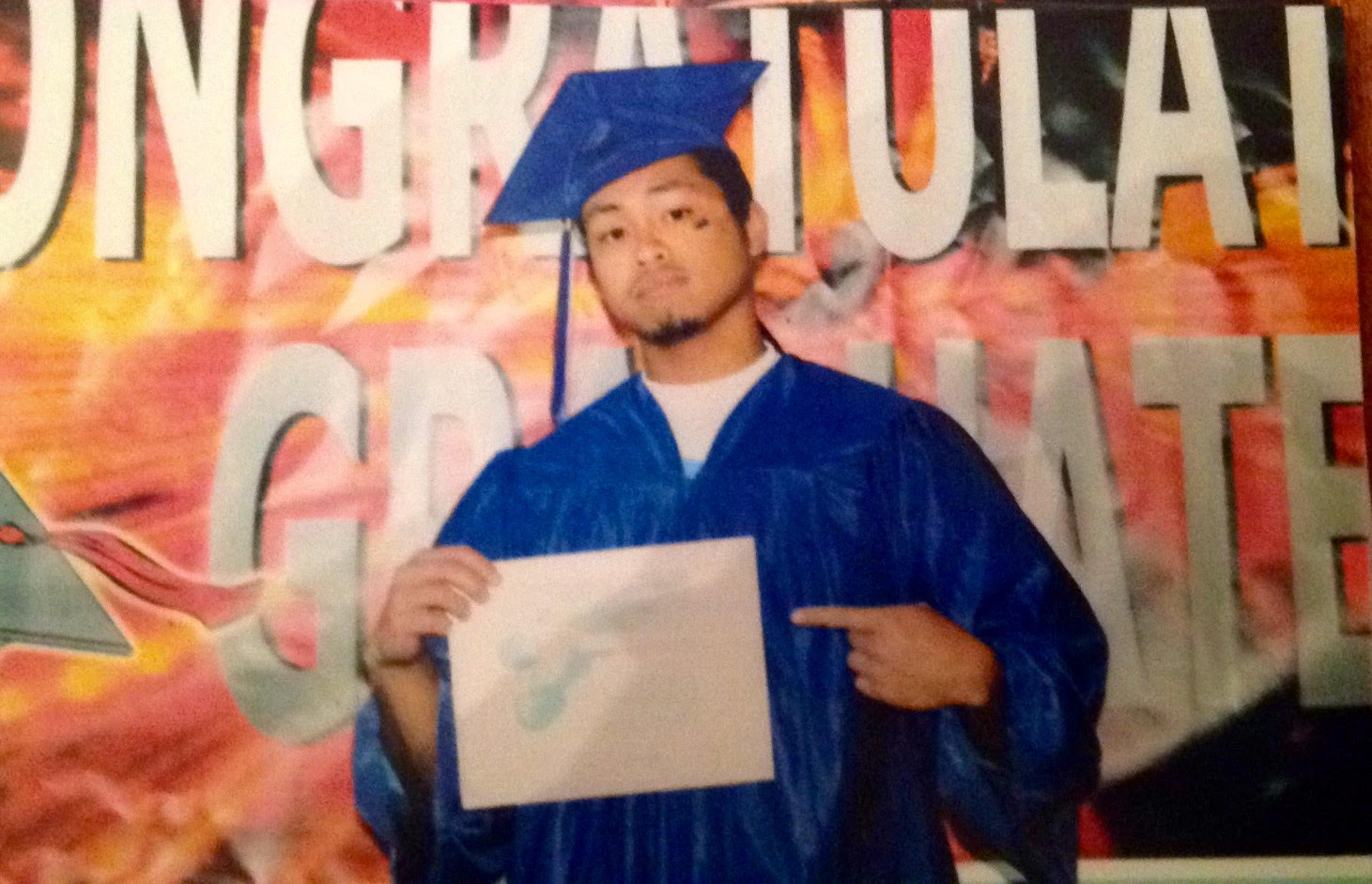

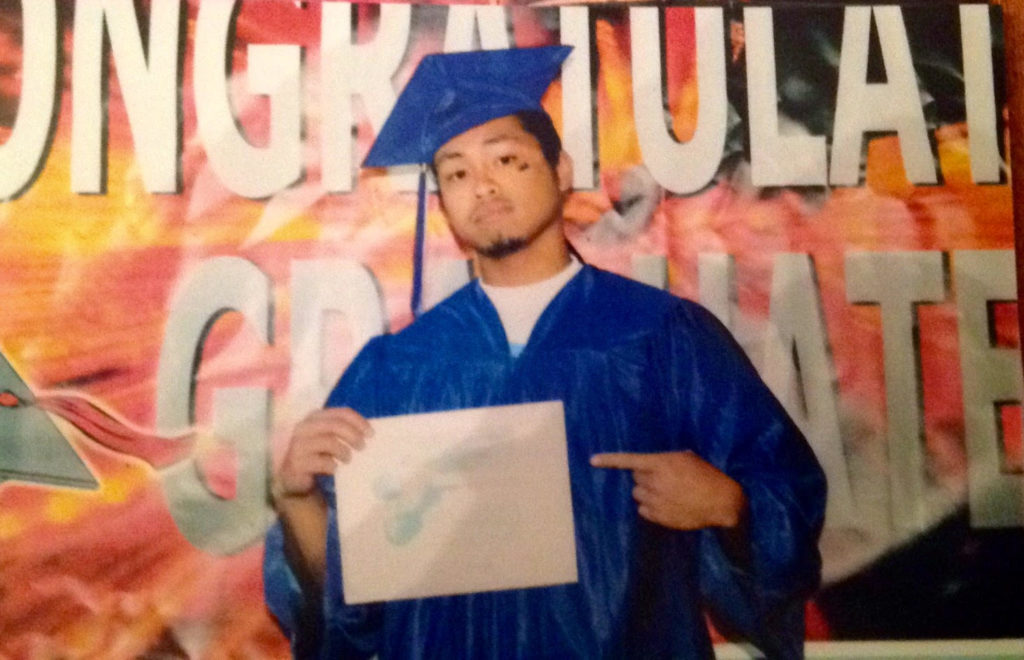

Since arriving at Kern Valley State Prison seven years ago, Lam Vo has completed his G.E.D. But his education has gone further than book knowledge. He’s come to accept his responsibility for a heinous crime and to understand the importance of becoming a moral human being.

“I understand that I must take accountability for my actions and that is why I am here in prison,” he wrote. “My endeavors were to be recognized and have people in the hood glorify me as the man. But now I perceive things differently.”

There’s a back story. Vo was a student of mine. I had wondered what happened to him after he didn’t return to school for the 11th grade. Perusing a newspaper article, I read that Vo had pleaded no contest to attempted homicide and faced 25 years in prison. I wrote to him, hoping he wasn’t the same Lam Vo. Sadly, he informed me he was. Over the years, we’ve stayed in touch — I talk to him weekly — and as an Oakland Voices correspondent in 2012, I wrote several articles about him.

When he arrived at Kern Valley State Prison, he had completed the 10th grade. During what would have been his 11th grade year, he became involved in gang activity and did not return to school. In November 2009 he was charged with attempted homicide. He had shot a girl in the head.

At Kern Valley, he completed his G.E.D. in June 2015 and is now planning to take classes at Coastline College.

The “School to Prison Pipeline” theory posits that schools are complicit in creating an environment in which certain students, particularly male students of color from poor or working class families, will almost certainly wind up in prison or some other form of detention.

Some prisons are working to connect the incarcerated to formal education, from completing high school to earning master’s degrees while serving their time. (Some studies show as many as 80 percent of those serving prison sentences are high school dropouts. Fewer than 10 percent have any college education; only about 5 percent have completed bachelor’s degrees.)

To increase their chances of being granted parole, inmates have opportunities to participate in a number of self-selected rehabilitative and educational programs. Toward that end, Vo completed his G.E.D and is participating in Criminals and Gang Members Anonymous (CGA), a 12-step program. “CGA is mainly composed of, but not only of, ex-gang members, recovering from a destructive lifestyle,” states the website. “We are addicted to destructive behaviors and lifestyle, including alcohol and drugs. We have firsthand experience — and know the end result of gang activity and destructive behavior is incarceration, physical impairment, or death.”

One of the steps is the completion of an Insight Questionnaire, which requires the participant to engage in an in-depth, soul searching or moral inventory. Vo mailed me a six-page, single-spaced handwritten copy of the questions and his responses.

He wrote that he got more involved in drugs and criminal activity when his family moved to East Oakland, and he felt the need to prove he was “tough.”

“Digging deep, I know the factors to the crime was fueled by doubt, worry, pride and loneliness,” he wrote about his state of mind after his girlfriend broke up with him and he was sent to juvenile detention for stealing a car and possessing a gun.

“Seven years ago, when I got arrested, I thought I was a good guy, pure and even cool. I came into prison getting involved with gang activities. That was until I got kicked around by them and that really helped push me to dropping out of the gang in 2011.”

“My life right now is in prison, but that does not deter me from being happy. I have family and friends to support me, and I understand there are people in the world that have nothing, so I feel bliss that I have discovered a change that will finally reveal my true self. The new me now is always looking for challenges.”

He said he would like to contact his victim; she survived the gunshot wound, but has permanent brain damage.

“Thoughts of how I caused Alicia, her family and my family pain, and the dream of seeing the world again have motivated me to stay away from people, places and things that trigger my negative impulses.”

It is not possible to know what is truly in the heart and mind of any human being, but sometimes we can consider their words, look into their behaviors, and try to see who and what is really there. Vo seems sincere in taking responsibility and wanting to be a constructive member of his community, both in prison, and perhaps, someday, beyond. He is aware of the egregious harm he has done.

“When I look back at what I did to Alicia, I feel troubled. I can’t believe that was me, and yet it was. I will never go back to being that person, so much pain I’ve caused to so many people,” he wrote. “I owe it to myself, society, Alicia and my family, to become a better model of being a human.”

Debora Gordon is a writer, artist, educator and non-violence activist. She has been living in Oakland since 1991, moving here to become a teacher in the Oakland Unified School District. In all of these roles, Debora is interested in developing a life of the mind. “As a mere human living in these simultaneously thrilling and troubled times,” Debora says, “I try to tread lightly, live thoughtfully, teach peace, and not take myself too seriously.”

Be the first to comment